In one spectacular monologue, Mister Señor Love Daddy recites his list of dozens of classical black musicians whose records he plays, beginning with Boogie Down Productions and ending with Mary Lou Williams. of a radio station operating from a storefront perch, where he’s on the air, watching the streets and orchestrating its moods with music, reporting back on what he sees and inflecting the moment with musings that connect the music to the community at large. Jackson, in the role of Mister Señor Love Daddy, the d.j. It begins with one of the cinematic voices of the era-with Samuel L. “Do the Right Thing” starts where Lee’s 1988 film “School Daze” ends-with a call to “Wake up”-but here it comes through by way of local media and in the context of art. The score was composed by Lee’s father, Bill Lee, a bassist who has recorded with many major jazz musicians and appears on a wide range of albums, including Clifford Jordan’s classic “ Glass Bead Games.” Lee’s artistic collaborations are central to the movie’s rich sense of an artistic gathering, including the cinematography of Ernest Dickerson, the production design, by Wynn Thomas, and the costume design, by Ruth E. They also evoke a cultural history-visual, dramatic, and tonal-informed by such artists as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin and John Coltrane. The movie’s bright palette, its sense of contrasts of light and color, its distinctive and prominent addresses by characters looking in high-relief and fish-eye closeup at the viewer, its sense of bold declamation and assertive movement: all suggest a personal sense of style that builds on the cinematically disjunctive methods of the nineteen-sixties.

“Do the Right Thing” is grand, vital, and mournful it is also, crucially, proud, a work not only of the agony of history-and of present-tense oppressions-but also of the historic cultural achievements of black Americans, and it takes its own place in the artistic history that it invokes. No less than Lee’s script, his aesthetic offers a sharply original way of looking at the lives of black people-and of looking at life at large from a black person’s perspective. The movie’s individuals are boldly sketched with expressive exaggerations, not characters with deeply developed psychology but ones who bear the marks, the scars, and the emblems of history, and who also bear the pressure of the white gaze, the police gaze. “Do the Right Thing” isn’t a comprehensive representation of a cross-section of Bedford-Stuyvesant, the Brooklyn neighborhood where it is set, but a vision of private lives with a conspicuous public component-a sense of community and of history that’s a crucial aspect of identity.

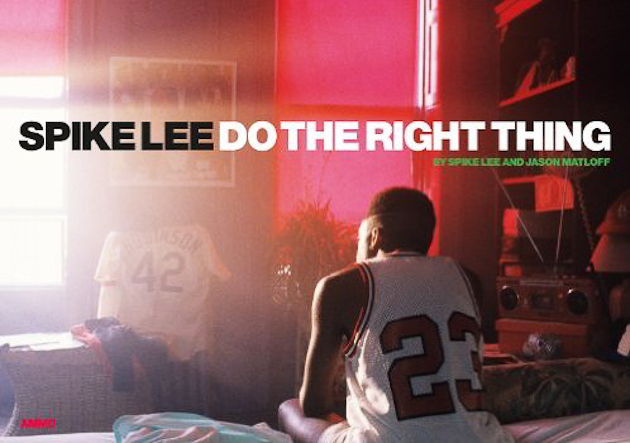

Spike lee do right thing movie#

Three decades later, with police forces virtually militarized and with the judicial system largely granting officers impunity for killings committed on duty, the shock of the movie is that, even as many cultural and civic aspects that it represents have changed, its core drama-the killing of black Americans by police-continues unabated and largely unredressed. Lee dedicated the movie, in the end credits, to the families of Eleanor Bumpurs, Michael Griffith, Arthur Miller, Edmund Perry, Yvonne Smallwood, and Michael Stewart-six black people, five of whom were killed by police officers, as the character Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) is, in the film’s climactic scene. Spike Lee’s third feature, “Do the Right Thing,” returns to movie theatres this weekend in honor of the thirtieth anniversary of its release.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)